Heart Attack Pain Locations: Chest, Left Arm, Jaw or Back?

Heart Attack Pain Locations: The Deadly Disconnect Between Perception and Physiology

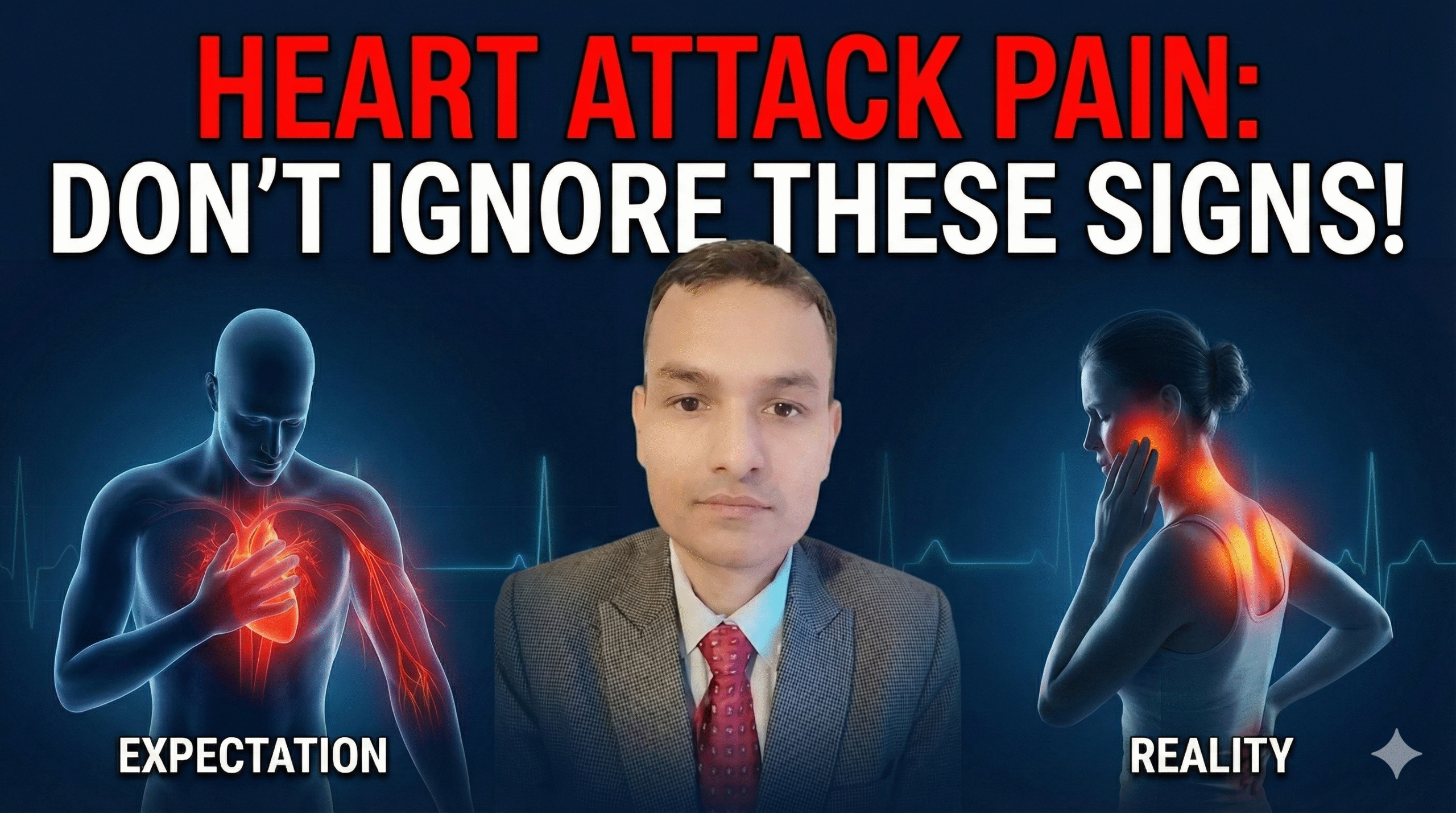

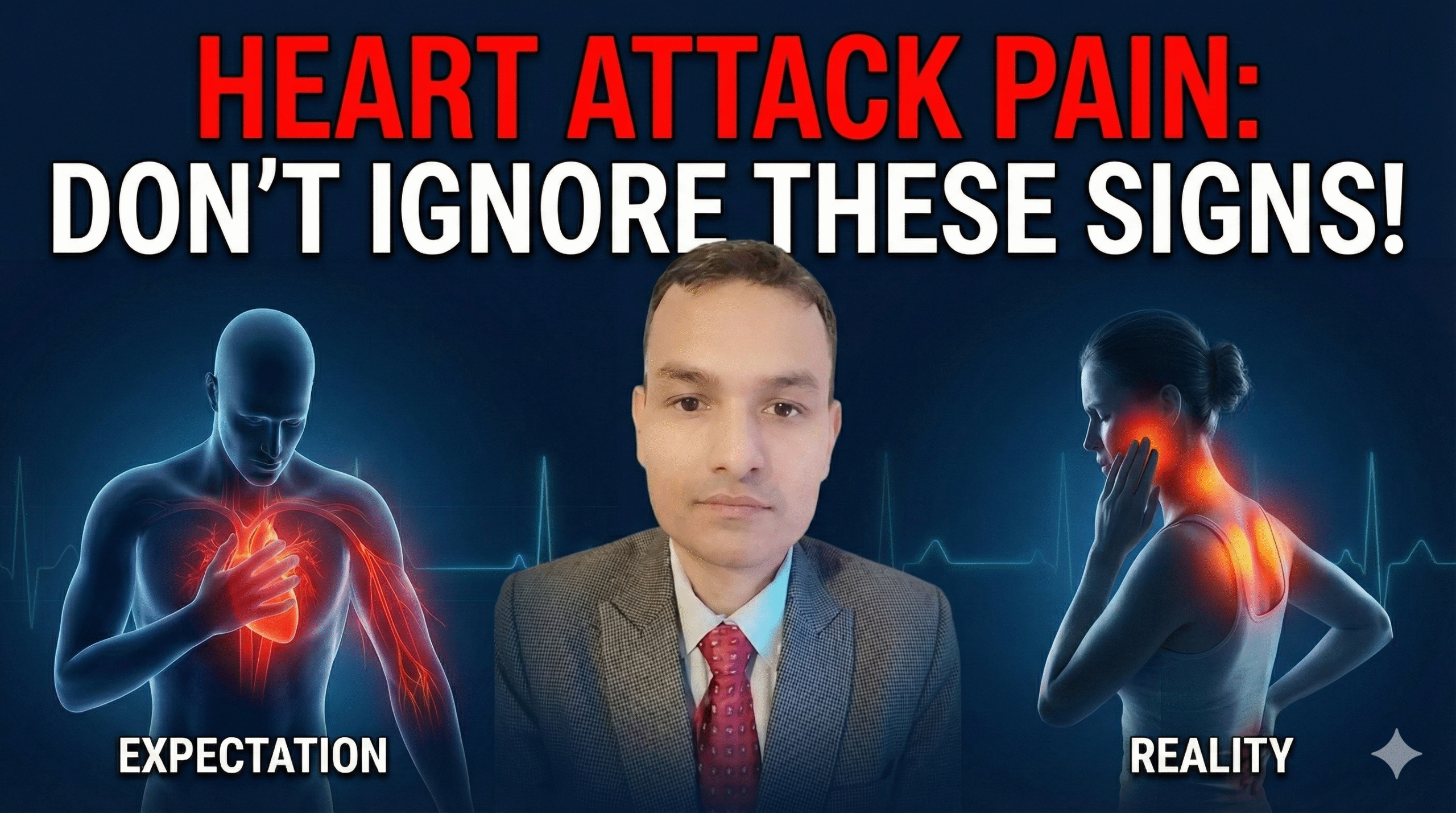

In the collective imagination, a heart attack is a singular, dramatic event: a person, usually a man, clutches the center of his chest, grimaces in agony, and collapses. This cinematic depiction, reinforced by decades of media, has created a dangerous cultural prototype. We are trained to look for the “Hollywood Heart Attack”—the crushing, undeniable pressure known clinically as the Levine Sign. Yet, the biological reality of myocardial infarction is far more subtle, deceptive, and geographically diverse. For millions of individuals, particularly women, the elderly, and those managing diabetes, the warning signs of a heart dying do not scream; they whisper. And frequently, they whisper from locations that seem entirely unrelated to the cardiovascular system: a dull ache in the jaw, a burning sensation in the upper back, or a numbness radiating down an arm.

The disconnect between the expected location of pain and the actual presentation of cardiac ischemia is a leading cause of pre-hospital delay. Patients often dismiss jaw pain as a dental issue, back pain as a musculoskeletal strain, or upper abdominal discomfort as indigestion. This report serves as a definitive, exhaustive guide to the geography of heart pain. Designed for the patients and practitioners at NexIn Health, it synthesizes current medical literature, neurophysiological mechanisms, and clinical data to dismantle the myths surrounding cardiac symptoms. We will explore the complex wiring of the human nervous system that leads to “referred pain,” analyzing why a problem in the chest manifests in the teeth. We will delve into the physiological nuances that make winter mornings particularly lethal, the silent threat facing diabetic patients, and the gender-specific variations that have historically led to the under-diagnosis of women. Furthermore, we will examine the spectrum of treatment options, contrasting traditional invasive procedures with advanced non-invasive therapies like Enhanced External Counterpulsation (EECP) that are redefining recovery.

Understanding these pain locations is not merely an academic exercise; it is a vital survival skill. The difference between recognizing interscapular pain as a sign of microvascular dysfunction rather than a pulled muscle can be the difference between seeking life-saving intervention and suffering irreversible heart muscle loss.

To comprehend why the heart hurts in the arm or jaw, we must first understand the architecture of the human nervous system. The phenomenon of referred pain—perceiving pain in a location distinct from the site of injury—is not a random malfunction but a predictable consequence of embryonic development and neural convergence.

The most widely accepted explanation for cardiac referred pain is the Convergence-Projection Theory. The human body possesses a vast network of sensory nerves, but the spinal cord does not have a dedicated, private line for every single organ to communicate with the brain. Instead, sensory information acts much like traffic merging onto a busy highway.

Visceral afferent nerve fibers, which carry signals from internal organs like the heart, enter the spinal cord at the same levels as somatic afferent nerve fibers, which carry signals from the skin and muscles. Specifically, the sensory nerves from the heart enter the spinal cord segments from T1 to T5. These are the exact same segments that receive sensory input from the medial (inner) aspect of the left arm, the left side of the chest, and the upper back.

When the heart muscle becomes ischemic (oxygen-starved), it releases chemical mediators such as bradykinin, adenosine, and lactate. These chemicals intensely stimulate the cardiac nerve endings. This barrage of pain signals floods the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The “second-order” neurons in the spinal cord, which are responsible for transmitting these signals up to the brain, become overwhelmed. Because the brain is accustomed to receiving frequent, harmless signals from the arm or chest wall (from touch or movement) but rarely receives signals from the heart, it defaults to the most common source. It “projects” the pain sensation onto the somatic map it knows best: the arm or the chest wall.

This neural confusion is the biological basis for the classic distribution of angina. The brain is essentially making a probability error, interpreting visceral distress as somatic injury.

While spinal convergence explains chest and arm pain, it does not fully account for symptoms like jaw pain, nausea, or the feeling of “doom.” These are mediated by the vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X). The heart is richly innervated by the vagus nerve, which provides parasympathetic control. When the heart—particularly the inferior wall which sits on the diaphragm—is damaged, it triggers intense vagal afferent signaling.

The vagus nerve terminates in the brainstem, specifically in the nucleus of the solitary tract. This region sits in close proximity to the nuclei of other cranial nerves, including the trigeminal nerve (Cranial Nerve V), which supplies sensation to the face and jaw. The “crosstalk” between the vagal input from the heart and the somatic input from the face can lead the brain to perceive cardiac distress as pain in the lower jaw, teeth, or neck. Furthermore, vagal overstimulation is responsible for the intense nausea, vomiting, and diaphoresis (sweating) that often accompany heart attacks, mimicking gastrointestinal illness.

Chronic cardiac conditions can actually alter the structure of the nervous system, a phenomenon known as central sensitization. Continuous bombardment of pain signals from the heart can lower the threshold of the spinal neurons, making them hypersensitive. This means that even minor stimuli from the chest wall or arm—which would normally be ignored—are interpreted as pain. This sensitization can lead to a widening of the referred pain field, causing pain to spread from the chest to the back, neck, or even the right arm. It explains why patients with long-standing angina may have more diffuse and unpredictable pain patterns than those experiencing a sudden, acute event.

Despite the importance of atypical symptoms, the chest remains the most common location for heart attack pain in both men and women. However, the quality and nature of this pain are often misunderstood, leading to dangerous reassurances.

True cardiac pain, or angina pectoris (Latin for “strangling of the chest”), is rarely described as “pain” in the conventional sense of a sharp, stabbing sensation. Patients, when asked to describe their symptoms, often use visceral descriptors: squeezing, crushing, heaviness, tightness, or a sensation of a heavy weight, often invoking the image of an “elephant sitting on the chest”.

This sensation is so characteristic that Dr. Samuel Levine, a pioneer in cardiology, noted that patients would frequently clench their right fist over their sternum when describing it. This clenched-fist gesture, the Levine Sign, has a high positive predictive value for ischemia. The pain is usually retrosternal (behind the breastbone) and diffuse. A patient cannot point to it with one finger. If a patient can localize the pain to a pinpoint spot that can be reproduced by pressing on the chest wall, it is statistically less likely to be cardiac, though this rule is not absolute.

From this central epicenter, the pain radiates outward, following the dermatomal maps of the T1-T5 spinal nerves.

Transmural Radiation: The pain may feel as if it is piercing through the chest to the back. This “through-and-through” pain can also be a sign of aortic dissection, a critical differential diagnosis.

Superior Radiation: The pain moves upward into the neck and throat, often described as a choking sensation or a tightness in the collar area.

Lateral Radiation: The pain spreads across the chest wall to both shoulders, creating a sensation of a “cape” of heaviness.

Contrary to the belief that heart attack pain is a sudden, continuous thunderclap, many events begin with “stuttering” symptoms. A patient might feel chest tightness while walking quickly (exertional angina) that resolves with rest. Hours later, it returns with less exertion. This pattern indicates a plaque that is becoming increasingly unstable—perhaps a thrombus is forming and dissolving repeatedly. This “crescendo angina” is a critical warning phase where intervention can prevent massive myocardial loss. Ignoring these fluctuating chest symptoms because “they went away” is a common error.

The association between the heart and the left arm is perhaps the most well-known medical fact in the lay population, yet the nuances of this presentation are frequently overlooked.

The classic radiation to the left arm follows the distribution of the ulnar nerve. Patients typically report pain or sensation running down the medial (inner) aspect of the upper arm, through the elbow, and down the forearm into the wrist, ring finger, and little finger. This specific pathway exists because the sensory fibers from the medial arm enter the spinal cord at T1, the same level as the primary cardiac fibers.

The sensation in the arm is not always “pain.” It is often described as:

Numbness or Tingling (Paresthesia): A “pins and needles” sensation, similar to when a limb falls asleep.

Heaviness or Weakness: The arm feels like dead weight; the patient may struggle to lift it.

Dull Ache: A deep, bone-weary ache that does not improve with massaging or repositioning the arm.

While left arm pain is a strong indicator of cardiac etiology, the absence of left arm pain does not rule out a heart attack. Furthermore, pain in the right arm or both arms is also a significant cardiac symptom. In fact, some studies suggest that pain radiating to both arms is an even more specific indicator of acute myocardial infarction than left arm pain alone.

The heart is a central organ, and while it sits predominantly in the left thoracic cavity, its innervation is not strictly unilateral. Bilateral shoulder or arm pain, especially when accompanied by chest pressure or shortness of breath, should never be dismissed as arthritis or muscle strain. In women specifically, radiating pain to both arms is a documented variation that is often missed.

One of the most perilous masquerades of myocardial infarction is craniofacial pain. It is a tragedy of modern medicine that patients suffering from a life-threatening cardiac event often seek help from a dentist or an ENT specialist before a cardiologist.

As detailed in the neurology section, the referral of pain to the jaw is driven by the convergence of vagal afferents and the trigeminal nerve system. This creates a sensation of pain in the mandible (lower jaw), the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), and the teeth. Importantly, cardiac pain almost never radiates above the nose. Pain in the forehead, eyes, or top of the head is unlikely to be cardiac. The danger zone is the lower jaw and neck.

How does one distinguish a cardiac “toothache” from a dental one?

Triggers: Dental pain is typically provoked by thermal stimuli (hot or cold fluids) or mechanical pressure (chewing, tapping on the tooth). Cardiac jaw pain is provoked by exertion or emotional stress. If walking up a flight of stairs causes your jaw to ache, and stopping causes the ache to subside, the pathology is likely vascular, not dental.

Bilaterality: Dental problems are usually localized to a specific tooth or side. Cardiac jaw pain is often bilateral (felt on both sides of the jaw) or left-sided. Isolated right-sided jaw pain is rarely cardiac.

Associated Symptoms: A tooth infection rarely causes breathlessness, cold sweats, or nausea. If jaw pain is accompanied by these systemic signs, it is an emergency.

Some patients describe a sensation of constriction in the throat, often grabbing their neck in a gesture distinct from the chest-clutching Levine sign. This can be mistaken for an allergic reaction or anxiety. However, “throat tightness” is a well-documented anginal equivalent, representing the upward radiation of the visceral “strangling” sensation from the chest.

Back pain is one of the most common complaints in adult medicine, usually attributed to musculoskeletal causes. However, in the context of cardiac ischemia, it serves as a critical, often ignored, warning sign, particularly for women.

Cardiac back pain is typically centered in the interscapular region—the area between the shoulder blades. It reflects the posterior innervation of the heart and the sharing of dorsal root ganglia at the thoracic levels. Unlike muscular back pain, which is usually sharp, reproducible with movement, and relieved by massage, cardiac back pain is deep, burning, or aching. It is often described as a “rope being tightened” around the upper chest.

Research consistently shows a gender divide in this symptom. Women are significantly more likely than men to report back pain as a primary or concurrent symptom of a heart attack. One study analyzing gender differences found that women had a notably higher prevalence of back pain (up to 42-72% in some cohorts) compared to men. This discrepancy contributes to the misdiagnosis of women in emergency settings, where back pain is often triaged as non-urgent musculoskeletal strain.

For women, especially those with risk factors like diabetes or hypertension, sudden onset back pain that is not linked to a specific injury or physical activity should be treated with high suspicion. If the back pain wakes a patient from sleep or persists at rest, it warrants cardiac evaluation.

The proximity of the heart to the stomach, separated only by the thin muscle of the diaphragm, creates a zone of diagnostic confusion that is responsible for countless missed heart attacks.

The inferior wall of the heart rests directly on the diaphragm. When this area becomes ischemic (an inferior wall myocardial infarction), the pain is often referred downwards into the epigastrium (the upper central region of the abdomen). This mimics the sensation of acid reflux, gastritis, or peptic ulcer disease. Patients often report a burning sensation, bloating, or a “gnawing” pain in the pit of the stomach.

Patients frequently attribute this sensation to “gas” or “something I ate.” This denial is a powerful psychological defense mechanism; it is far less frightening to have indigestion than a heart attack. However, there are key differentiators:

Response to Antacids: True GERD or indigestion usually responds, at least partially, to antacids, burping, or standing upright. Cardiac epigastric pain is unrelenting; it does not improve with burping or Maalox.

Systemic Symptoms: “Gas” does not typically cause diaphoresis (cold sweats), hypotension (lightheadedness), or exertional dyspnea. The combination of stomach pain and a cold sweat is a classic presentation of an inferior MI (often involving the Right Coronary Artery).

As discussed, the vagus nerve is heavily involved in inferior wall infarctions. This vagal stimulation triggers the vomiting center in the brain. Nausea and vomiting are present in a significant proportion of heart attacks, particularly in women (up to 53% vs. 29% in men). This presentation is frequently misdiagnosed as viral gastroenteritis (stomach flu), especially if chest pain is absent or mild.

If the diverse locations of pain create a “language barrier” for diagnosis, diabetes creates a “broken transmitter.” For the millions of people living with diabetes, the neural alarm system that warns of cardiac damage is often fundamentally compromised.

High blood glucose levels over time cause systemic damage to nerve fibers, a condition known as diabetic neuropathy. While most commonly associated with numb feet, this damage also affects the autonomic nervous system, including the sensory nerves of the heart (Cardiac Autonomic Neuropathy). This damage can block the transmission of pain signals from the ischemic heart to the brain.

The result is Silent Ischemia or a Silent Myocardial Infarction. A diabetic patient can undergo a massive heart attack with total coronary occlusion and feel absolutely no chest pain, arm pain, or jaw pain. Studies indicate that nearly 45% of heart attacks may be silent, and the prevalence is disproportionately high in the diabetic population. These patients often present late, only after signs of heart failure (fluid overload, severe breathlessness) have set in, leading to significantly higher mortality rates.

Since “pain” is an unreliable metric for this population, patients and clinicians must be vigilant for Angina Equivalents—symptoms that serve as a proxy for pain.

Dyspnea (Shortness of Breath): Sudden, unexplained breathlessness is the most common equivalent. If a diabetic patient finds themselves winded after walking a distance that was previously comfortable, or wakes up gasping for air, it is a cardiac red flag.

Diaphoresis: Profuse sweating without exertion or fever.

Extreme Fatigue: A sudden onset of lethargy or weakness, often described as “feeling like the battery has been pulled out.”

Unexplained Hyperglycemia: A sudden spike in blood sugar levels can be a physiological response to the stress of an infarction.

NexIn Health emphasizes that for diabetic patients, any sudden change in functional capacity should be investigated as cardiac until proven otherwise.

The historical bias of medical research towards male subjects has created a “textbook” definition of heart attack symptoms that fails to capture the female experience. This has led to the “Yentl Syndrome,” where women are under-diagnosed and under-treated because their symptoms do not match the male prototype.

While men typically develop obstructive coronary artery disease (blockages in the main arteries), women are more prone to Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction (CMD) and Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA). In these conditions, the tiny arterioles that regulate blood flow within the heart muscle fail to dilate properly. Because these vessels are too small to be seen on a standard angiogram or fixed with a stent, women are often told their arteries are “clean” despite suffering from severe ischemia.

The pain from microvascular disease is often more diffuse than the localized pain of a major artery blockage. It may present as generalized chest discomfort, burning, or exhaustion rather than the crushing “elephant” pressure. This physiological difference drives the variation in symptom presentation.

Women are more likely to experience prodromal (warning) symptoms in the weeks leading up to a heart attack. Research indicates that 95% of women experience new or different symptoms a month or more before their event.

Unusual Fatigue: Reported by over 70% of women.

Sleep Disturbances: Difficulty falling or staying asleep.

Anxiety: A distinct sense of doom or anxiety that is unrelated to life stressors. Recognizing these prodromal signs offers a window of opportunity for prevention that is often missed.

Heart attacks are not random events; they are influenced by environmental physics and biological rhythms. Understanding when a heart attack is most likely to occur can help in recognizing the symptoms.

Winter is the deadliest season for cardiovascular health. NexIn Health data and global studies confirm a spike in heart attack rates of 31% to 50% during cold months. This is driven by the Cold Pressor Response: cold air hitting the skin triggers immediate vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels) to conserve heat. This drastically increases blood pressure (afterload), forcing the heart to work harder against higher resistance.

Simultaneously, winter causes hemoconcentration. To reduce heat loss, the body reduces fluid volume (“cold diuresis”), leading to thicker, more viscous blood with higher concentrations of clotting factors like fibrinogen. This “sludge-like” blood is more prone to clotting in narrowed arteries.

The risk of myocardial infarction peaks between 6:00 AM and 12:00 PM. This correlates with the body’s circadian rhythm. Upon waking, the body releases a surge of cortisol and catecholamines (adrenaline) to mobilize energy for the day. This causes a rapid rise in heart rate and blood pressure—the Morning Surge. For a patient with a fragile plaque, this sudden hydraulic stress can cause rupture. In winter, the combination of the morning surge and cold vasoconstriction creates a “double whammy” of risk.

Psychological stress also plays a role. The “Monday Peak” in heart attacks is a documented phenomenon, attributed to the stress of returning to the work week. The transition from weekend relaxation to weekday stress triggers sympathetic activation, which can tip a vulnerable cardiovascular system over the edge.

Once symptoms are recognized and a diagnosis is made, the patient faces a complex landscape of treatment options. Traditionally, the choice has been between medication and invasive revascularization (stents or bypass). However, the emergence of non-invasive therapies like EECP offers a new paradigm, particularly for patients with microvascular disease or high surgical risk.

Angioplasty (PCI): Involves threading a catheter into the heart to place a stent that props the artery open. It is the gold standard for acute STEMI (heart attack in progress) to restore flow immediately. However, in stable disease, particularly in diabetics, stents have a risk of restenosis (re-narrowing).

Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG): Open-heart surgery where a vein or artery is harvested to bypass the blockage. The BARI trial showed that for diabetics with multi-vessel disease, CABG offers better survival than stents. However, it carries significant risks of infection, stroke, and prolonged recovery, especially in the elderly.

Enhanced External Counterpulsation (EECP) is a core offering at NexIn Health. It acts as a “natural bypass” for patients who are not candidates for surgery or who wish to avoid invasive risks.

Mechanism: Pneumatic cuffs on the legs inflate during diastole (heart rest), forcefully pumping oxygenated blood back to the heart, and deflate during systole (heart pump), creating a vacuum that unloads the heart’s work.

Angiogenesis: This mechanical shearing force stimulates the release of growth factors like VEGF, promoting the growth of new collateral blood vessels. It essentially grows a biological bypass around the blockages.

Role in Microvascular Disease: Unlike stents, which only fix large focal blockages, EECP improves flow throughout the entire vascular tree, making it uniquely effective for the diffuse microvascular disease common in women and diabetics.

| Feature | Medical Therapy (OMT) | Bypass Surgery (CABG) | EECP Therapy (NexIn Focus) |

| Invasiveness | Non-invasive | Highly Invasive (Sternotomy) | Non-Invasive (External Cuffs) |

| Mechanism | Chemical Blockade | Mechanical Bypass | Hemodynamic Augmentation |

| Recovery | None | 3-6 Months | None (Outpatient) |

| Risk Profile | Side effects of drugs | Stroke, Infection, Mortality | Minimal (Skin irritation) |

| Target Disease | Systemic | Macrovascular (Large vessels) | Macro & Microvascular |

| Cost (India) | Recurring | High (₹3 – 6 Lakhs) | Moderate (₹70k – 1.2 Lakhs) |

NexIn Health advocates for a holistic approach that combines advanced technology with ancient wisdom to support heart health.

Ayurvedic Support:

Arjuna (Terminalia arjuna): Clinically shown to strengthen heart muscle contraction and improve endothelial function.

Garlic: Acts as a natural anti-platelet agent, helping to thin the “thick blood” of winter.

Ashwagandha: Modulates cortisol, helping to blunt the dangerous “Morning Surge”.

Homeopathic Support:

Crataegus (Hawthorn): Known as a heart tonic, it helps regulate blood pressure and improve coronary flow.

Digitalis: Used in homeopathic dilutions for palpitations.

Lifestyle:

Thermal Regulation: The “3-Layer Rule” for clothing to prevent cold pressor response.

Hydration: Maintaining blood volume to prevent hemoconcentration.

Morning Caution: Avoiding high-intensity exertion immediately upon waking.

The geography of heart pain is complex, mapping onto the body in ways that defy intuition. The pain in the jaw, the ache in the back, the numbness in the arm—these are not random symptoms but precise neurological signals of a heart in distress.

For women, understanding that back pain and fatigue are “typical” for their biology is a critical step toward gender equity in health outcomes. For diabetics, recognizing the “silent” signs of breathlessness and sweating is a matter of life and death. For everyone, acknowledging that the “Hollywood Heart Attack” is a myth allows for earlier intervention.

At NexIn Health, we believe that the future of cardiac care lies in this deep understanding—combining the ability to recognize subtle symptoms with the power of non-invasive therapies like EECP to restore health without trauma. By listening to the whisper of the heart today, we can prevent the silence of tomorrow.

Disclaimer:

This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always seek immediate emergency medical attention for suspected heart attack symptoms. Consult a cardiologist before starting any new therapy or supplement.